Convergent is a product of Leap Orbit LLC | Copyright© 2023

by Jake Tunney, Business Development Manager, Leap Orbit

On October 5th, CMS published an RFI for a National Directory of Healthcare Providers and Services or “NDH.” The NDH would create a “centralized data hub” to once-and-for-all solve the problem of inaccurate provider directories. We applaud CMS’s intention to tackle this perennial, thorny challenge and welcome the chance to provide feedback given our deep experience working with payers, state Medicaid agencies, state-run benefits exchanges, and HIEs in this domain.

Leap Orbit is a healthcare interoperability-focused enterprise technology company founded in 2015. Our vision is to build best-in-class solutions for the healthcare market, using the most modern tools, cutting edge platforms, and modular components under a single umbrella. Since our founding, Leap Orbit has lived up to this vision. Our first major product, a prescription drug motioning platform, is live in Maryland, Nebraska, and Utah, and is being implemented in New Brunswick, Canada.

Our provider directory tool, the Convergent Provider Data Hub, is Leap Orbit’s fastest growing business component. After significant multi-year research and development, we launched Convergent in 2020. Since the launch, our customers in government and the private sector have employed Convergent to rethink the way healthcare provider data is managed and exchanged. We help them navigate the rapidly changing regulatory environment, where accurate provider data is quickly becoming critical infrastructure. We are investing significant resources to expand features to the industry’s premier provider data management platform-as-a-service . We currently cover over 6.1 mm providers with hundreds of different provider types.

Convergent supports the following use cases:

In many ways, the architecture of Convergent reflects the vision that CMS has begun to articulate for the NDH, albeit at the enterprise (and not federal agency) level. Even should a successful NDH be rolled out over time, we do not expect it to alleviate the need for healthcare organizations to maintain their own, interoperable provider data management systems like Convergent. What we envision is a more seamless, well-connected set of provider data sources that rely on key sources of truth, like the NDH, to present accurate and up-to-date provider information where and when it’s needed. We hope that CMS finds our perspective valuable and look forward to continued dialogue on this important topic.

The RFI rightly points out some fundamental problems with current efforts surrounding provider directories:

Although these are all significant problems, we view the first item—inefficient, redundant reporting from providers—as the primary problem, and items two through five are symptoms of that problem. Case in point: on average, provider practices have 20 health plan contracts that require regular status and demographic updates.[1] Each of these has different standards for reporting updates. Many providers have expressed a desire for health plans to align on fewer update channels.[2]

We think addressing this problem is the biggest opportunity presented by this RFI. Resolving redundant reporting channels would be a significant challenge but a massive win for the healthcare industry. But in many key ways, CMS is uniquely positioned to drive the solution. Through tools such as the Quality Payment Program and its authority to regulate state Medicaid programs, Medicare Advantage and other key aspects of the industry, CMS has at its disposal the “carrots and sticks” necessary to bring major change. If CMS is successful, progress on the other use cases identified in the RFP can more easily follow. By solving this central problem, CMS would also establish its credibility in the provider data domain, whereas if it attempts to tackle too many challenges or use cases at once and fails this credibility will be damaged—e.g. CMS will be seen as a part of the problem and not bringing solutions.

For this reason, we strongly suggest CMS take a phased approach, beginning with provider reporting to payers and others and proceeding incrementally by building on demonstrable success. As one example, given our work with HIEs and other customers on interoperability initiatives, we appreciate CMS’s interest in improving access to providers’ digital endpoints, supporting record location for digital exchange, and driving adoption of the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA). However, we see the complexity of this area and interdependencies with so many other agencies and stakeholders making it a risky set of use cases to pursue at the same time as the one we have recommended above. This is not to say the NDH couldn’t have a role to play; rather, we would advise addressing this area down the road as CMS builds on prior foundational successes.

Below are responses to the questions we believe our experience qualifies us best to respond to.

What benefits and challenges might arise while integrating data from CMS systems (such as NPPES, PECOS, and Medicare Care Compare) into an NDH? What data elements from each of these systems would be important to include in an NDH versus only being available directly from the system in question?

One challenge will always be merging data from disparate data sources and resolving duplicates. Where data sets have NPI that will be less of a problem. However, there are other datasets like state boards that do not have an NPI.

Another challenge is determining which data elements from which source to prioritize over another. For example, do we take specialty from Medicare Care Compare, or from NPPES. Please see “Attachment: CMS & NPPES Data Mapping” for detail on which fields are relevant within the NDH.

An obvious benefit is the convenience of accessing one API to pull all relevant data.

Are there other CMS, HHS (for example, HPMS, Title X family planning clinic locator, ACL’s Eldercare Resource Locator, SAMHSA’s Behavioral Health Resource Locator, HRSA’s National Practitioner Data Bank, or HRSA’s Get Health Care), or federal systems with which an NDH could or should interface to exchange directory data?

The core data sets mentioned above are an obvious fit. As datasets expand there need to be explicit use cases that require them. Our view is that the datasets above would initially be consumers of the NDH source of truth data for core provider data attributes. Long-term, NDH may look to add additional, differentiated attributes from these sources.

Are there systems at the state or local level that would be beneficial for an NDH to interact with, such as those for licensing, credentialing, Medicaid provider enrollment, emergency response (for example, the Patient Unified Lookup System for Emergencies (PULSE) [73] ) or public health?

Yes, these all could be relevant depending on the use cases of the NDH. However, if the NDH’s initial use case is to resolve redundant provider reporting, we recommend not starting with the state or local level data sets. The core data elements required to facilitate demographic updates and the number of reporting channels are included in “Attachment: Core NDH Fields.”

What types of data should be publicly accessible from an NDH (either from a consumer-facing CMS website or via an API) and what types of data would be helpful for CMS to collect for only internal use (such as for program integrity purposes or for provider privacy)?

Also included in “Attachment: Core NDH Fields” in column Public/Private.

We have heard interest in including additional healthcare-related entities and provider types beyond physicians in an NDH-type directory beyond those providers included in current CMS systems or typical payers’ directories? For example, should an NDH include allied health professionals, post-acute care providers, dentists, emergency medical services, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, certified nurse midwives, providers of dental, vision, and hearing care, behavioral health providers (psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, licensed professional counselors, licensed clinical social workers, etc.), suppliers, pharmacies, public health entities, community organizations, nursing facilities, suppliers of durable medical equipment or health information networks? We specifically request comment on entities that may not currently be included in CMS systems.

We recommend covering as many provider types as possible. The Medicare FFS Public Provider Enrollment Data Dictionary outlines a set of Provider Type Codes that can be used to enforce conformance around a common set of provider types.

We want an NDH to support health equity goals throughout the healthcare system. What listed entities, data elements, or NDH functionalities would help underserved populations receive healthcare services? What considerations would be relevant to address equity issues during the planning, development, or implementation of an NDH?

There are a number of accessibility features that providers may offer including handicap accessibility, ADA compliance, public transit options, answering service, cognitive support services, and mobility services. Oregon is at the forefront of collecting what is known as “REALD” data which includes race, ethnicity, languages, and disabilities.

What provider or entity data elements would be helpful to include in an NDH for use cases relating to patient access and consumer choice (for example, finding providers or comparing networks)?

What data elements would be useful to include in an NDH to help patients locate providers who meet their specific needs and preferences?

Would it be helpful to include data elements such as provider languages spoken other than English, specific office accessibility features for patients with disabilities and/or limited mobility, accessible examination or medical diagnostic equipment, or a provider’s cultural competencies, such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s Health Equity accreditation (though we note that these data elements may be difficult to verify in some cases)?

Yes

Understanding that individuals often move between public and commercial health insurance coverage, what strategies could CMS pursue to ensure that an NDH is comprehensive both nationwide and market-wide?

CMS, or a federal partner, should examine how to require all plans to publish their directory in a FHIR API; the NDH should then consume that data for plan participation information for each provider.

How should CMS work with states to align federal and state policies to allow all parties to effectively use an NDH?

States are primarily medical license and sanctions issuers. Today there is no unified source of that information. While this data is not necessarily a demographic update, a central repository would be a huge improvement to the current state of affairs. FSMB has already begun this work and could be a viable partner with collecting licensing data on all 50 states.

What types of entities should be encouraged to use data from an NDH? For what purposes and why?

We envision an environment where all providers who receive payment from Medicare are incentivized to keep their information up-to-date in the NDH. Currently, many providers are encouraged to use the ProView tool from CAQH for this purpose (payers are given free access to data feeds from ProView); however, this use is not ubiquitous and CAQH does not possess the same “carrots and sticks” that CMS does to motivate providers to use it.

If this environment became reality, we believe payers would in turn use the NDH as a single source to verify demographic information and practice location information. This would begin to alleviate the major plan of multiple roster submissions and management that all providers and the payers with whom they contract must navigate today. This is a major source of friction and bad outcomes in the provider data domain.

What are some of the functions or features of current provider directories that work particularly well?

What are some of the lessons learned or mistakes to avoid from current provider directories of which we should be aware?

We solicit comments on key considerations related to data submission and maintenance for potential NDH development: What policy or operational factors should be considered for new data collection interfaces as part of a single point of entry?

How can data be collected, updated, verified, and maintained without creating or increasing burden on providers and others who could contribute data to an NDH, especially for under-resourced or understaffed facilities?

CMS can pre-populate provider profiles using the data sources referenced above, and possibly also current claims. These profiles can then contain most of the data points that do not change often, with the ability for the provider to update information that might. We believe if CMS makes it a publicly-stated objective to quickly eliminate the friction providers and payers experience with roster management and tools like ProView, and replace this with a single, national source of truth in the NDH, then stakeholders will be motivated to support its success. Even under-resourced and understaffed organization experience this friction, and consolidating their effort around the NDH could be a meaningful and welcome burden reduction.

What are barriers to updating directory data in current systems that could be addressed with an NDH?

What are current and potential best practices regarding the frequency of directory data updates?

We recommend updating data as soon as a new source update is received. For example, NPPES publishes a weekly update file. The NDH should be able to ingest that information and populate it within the NDH within 24 hours of it being published.

What specific strategies, technical solutions, or policies could CMS implement to facilitate timely and accurate directory data updates?

How could consistent and accurate NDH data submission be incentivized within the healthcare industry?

With regard to providers themselves (both organizations and practitioners), CMS and HHS more broadly have a track record of creatively leveraging incentives to drive the implementation and use of new technologies. We see nothing different about the adoption of NDH. Just as CMS has made Promoting Interoperability requirements a key aspect of MIPS, so too could it incentivize timely, comprehensive reporting to the NDH as a vital part of the provision of quality care. Likewise, ONC should evaluate how to incorporate standards-based reporting to the NDH into future editions of its Standards Version Advancement Process (SVAP) so that relevant technology vendors to the provider community can contribute to enabling solutions.

Likewise, through its authority over state Medicaid programs and managed care as well as Medicare Advantage contracts, CMS can push plans to move towards contracts that require provider data management via the NDH instead of ad-hoc roster submission and third-party portals. Over time, all stakeholders would see gained efficiencies across contracting, credentialing, network building and management and IT.

How should duplicate information or conflicting information reported from different sources be resolved to balance the reporting burden versus confidence in data accuracy?

A cloud-based MDM platform like Convergent uses a matching algorithm to determine which providers are the same across different data sets. We apply a litany of strategies that result in a 99.9% match rate. The remaining duplicates are identified and resolved at the source. We then apply a series of ranking algorithms for each individual field including frequency, date, and source to determine which value at the field should be the “Golden Record.” Our preference is typically to use a data source ranking when we have a trusted primary source.

The Healthcare Directory initiative and FAST both identified validation and verification as important functions of a centralized directory. What data types or data sources are important to verify (for example, provider endpoint information, provider credentialing) versus relying on self-reported information? Are there specific recommendations for verifying specific data elements?

Typically, things like license, board certification, and insurance are verified by primary sources while demographic info and location are self-attested. NCQA’s credentialing standards are a useful framework when thinking about verification.

What use cases would benefit from data being verified and what sort of assurances would be necessary for trust and reliance on those data?

The NDH should focus its scope on being the primary source for self-attested data. Other use cases may arise in the future after this is successfully executed.

Self-attested data would require data provenance, indicating the date of the update, and the source of the update. The data source can either be the provider themselves or a delegated authority.

Are there use cases where an NDH could provide data that has already been verified to reduce that burden on payers or other entities and, if so, how could that be achieved?

Because demographic data and location data is self-attested, the NDH could be the single source of these updates.

What concerns might listed entities have about submitting data to an NDH? We solicit comments on provider delegation of authority to submit data on a provider’s behalf:

While REALD data could be useful, it might also be used to profile providers in a negative way. Awareness of racial and ethnic data could lead to discrimination.

What challenges, if any, occur in the processes for delegating authority to submit data on behalf of providers or in the processes for submitting directory data on behalf of providers?

A bulk upload from a physician group could be submitted that disagrees with what the provider themselves submit. The NDH needs to have an MDM system that enables a hierarchy of preferred data source rankings. In this case we’d want to rank the provider-submitted data over the group submitted data.

Should CMS consider including role-based access management to submit provider data to an NDH, and, if so, what kind of role-based access management?

Yes. HL7 has clear guidelines on identity and access management.

Are there entities that currently exist that would be helpful to serve as intermediaries for bulk data verification and upload or submission to an NDH? If so, are there existing models that demonstrate how this can be done (for instance, the verifications performed through the Federal Data Services Hub)?

Convergent for medical licenses, DEA #’s, Medicaid IDs, USPS Address standardization, OIG and SAM for sanctions, etc.

ABMS and other certification boards for board certification

How do intermediaries currently perform bulk data verification and upload or submission to provider directories?

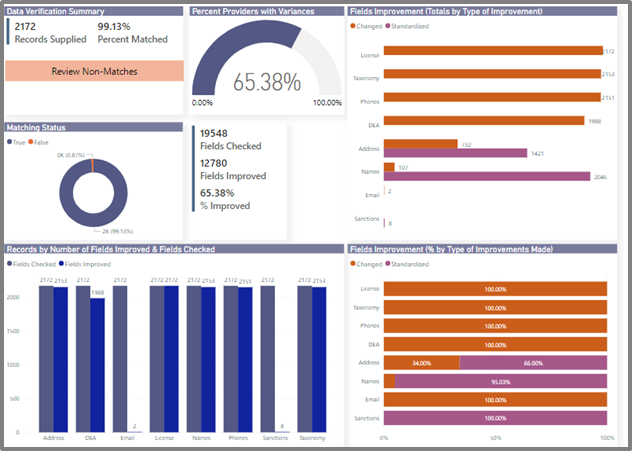

Convergent has a robust process, leveraging our search APIs to bulk query provider records against our nationwide set of reference data. We then auto-generate validation reports based on those results. Below is a sample report.

What functionality would constitute a minimum viable product?

What use cases should be prioritized in a phased development and implementation process for immediate impact and burden reduction?

Single location for provider practice location and demographic updates. It’s not even worth considering others until this is accomplished.

What types of entities and data categories should be prioritized in a phased development and implementation process for immediate impact and burden reduction?

All CMS provider types from this file (link) and all data elements under the Convergent-prescribed NDH Core Data Set.

How could human-centered design, including equity-centered design, principles be used to optimize the usability of an NDH?

We would recommend using the Design Sprint methodology established by Google Ventures (http://www.gv.com/sprint/). This provides a user-centric design approach that equally values expert input and end-user feedback.

What are the most promising efforts that exist to date in resolving healthcare directory challenges? How could CMS best incorporate outputs from these efforts into the requirements for an NDH? Which gaps remain that are not being addressed by existing efforts?

How could NDH use within the healthcare industry be incentivized? How could CMS incentivize other organizations, such as payers, health systems, and public health entities to engage with an NDH?

With regard to providers themselves (both organizations and practitioners), CMS and HHS more broadly have a track record of creatively leveraging incentives to drive the implementation and use of new technologies. We see nothing different about the adoption of NDH. Just as CMS has made Promoting Interoperability requirements a key aspect of MIPS, so too could it incentivize timely, comprehensive reporting to the NDH as a vital part of the provision of quality care. Likewise, ONC should evaluate how to incorporate standards-based reporting to the NDH into future editions of its Standards Version Advancement Process (SVAP) so that relevant technology vendors to the provider community can contribute enabling solutions.

Likewise, through its authority over state Medicaid programs and managed care as well as Medicare Advantage contracts, CMS can push plans to move towards contracts that require provider data management via the NDH instead of ad-hoc roster submission and third-party portals. Over time, all stakeholders would see gained efficiencies across contracting, credentialing, network building and management and IT.

[1]https://www.caqh.org/about/newsletter/2019/caqh-white-paper-hidden-cause-inaccurate-provider-directories

[2]https://www.caqh.org/sites/default/files/other/CAQH-AMA_Improving%20Health%20Plan%20Provider%20Directories%20Whitepaper.pdf

The Convergent Provider Data Platform reduces the costly burden of maintaining provider data. Convergent is a product of Leap Orbit, the trusted innovation partner to the leading health data networks.

Convergent is a product of Leap Orbit LLC | Copyright© 2023